Dónal Hassett, ‘Marseille’s Porte d’Orient: Commemoration of Conflict and Colonialism on the Mediterranean’s Northern Shore’

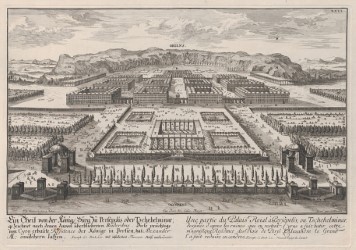

Perched on a promontory along the Corniche in Marseille’s salubrious quartiers sud, the Monument aux Héros de l’Armée de l’Orient et des terres lointaines represents an ambiguous lieu de mémoire of conflict and colonialism. Built to commemorate those who died while serving in French forces during the First World War on the Balkan fronts, at the Dardanelles, and in colonial spheres of the conflict, the monument, commonly known as the Porte d’Orient, does de-centre the Western front in commemorative discourse and underline the global nature of the conflict. However, the symbolism embedded in the sculptural form of the monument and the subsequent commemorative interventions on the site elide the centrality of coercive system of colonialism to the histories of violence it claims to memorialise. This selective silence raises broader questions about cosmopolitan modes of commemoration on the Mediterranean’s Northern Shore, both past and present, that elevate limited conceptions of diversity over the harsh realities of domination and discrimination rooted in colonialism and the resistance which they have provoked. Marseille’s status as the principal port of the French empire is embedded [...]