The production of pictorial, sculptural and engraved portraits greatly fostered knowledge of the Other. Effigies of African natives, Moors, slaves, Turks and ambassadors from distant lands helped to entrench or change certain opinions, while reshaping the image of Europe itself, which has always been multicultural and host to a constant struggle between its self-perception as an uncorrupted unicum and the reality of vital and inevitable exchange with other cultures. Images of the Other also penetrated Baroque Europe due to the widespread diffusion of engravings: a phenomenon that can be analysed through a selection of case studies. One of the best known is the representation of Antonio Manuel, Marquis Ne Vunda, ambassador of King Alvaro II of the Congo. He arrived in Rome in 1608 and after his death was celebrated with engravings and a magnificent funeral monument with an outstanding polychrome marble portrait in Santa Maria Maggiore. Another example which has not entered the critical debate to such an extent is provided by Moulay Al-Rashid ibn Sharif, sultan of Morocco from 1666 to 1672. Known as the Great Tafiletta, his likeness appears in several engravings in which he constantly changes appearance, always poised between a European identity and a more authentically Moroccan one. The biography of Tafiletta appears in several successful volumes in which he is identified as an extraordinary fighter, with exceptional physical and intellectual gifts. Of these, Antoine Charant’s Histoire de Muley Arxid, Roy de Tafilete, Fez, Maroc & Tarudent was published in Paris in 1670. The numerous editions suddenly printed in different languages, from English to German and Italian, demonstrated the interest aroused by this unusual figure, who came from the African continent and took on the traits of a mythical hero in contemporary European literature. In the Italian edition printed in Bologna in 1670, the Vera Istoria del principe Tafiletto, he is described as having a complexion “a shade darker than olive and almost black. The features of his face are of such proportions that his air and physiognomy show him to be of great, especially martial quality that makes him majestic and highly respected throughout the world”.

To identify Moulay Al-Rashid, the image chosen for the first book published in London in 1669, A Short and Strange Relation of Some Part of the Life of Tafiletta, was the one drawn by Flemish artist Abraham van Diepenbeeck and engraved by Adriaen Lommelin in Antwerp in 1660. Portraying the mysterious and appealingly mythical “Ginnaeghel Aethiopiae et Magnae Aegypciae Rex” (Fig. 1), it was evidently chosen by the publisher (T.N., probably Thomas Newcombe) in the absence of other images depicting the sovereign.

Figure 1: Abraham van Diepenbeeck and Adriaen Lommelin, Ginnaeghel Aethiopiae et Magnae Aegypciae Rex, 1660, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum. © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

He shows unmistakably African features and apparel, such as the jewellery and the turban, that mixed Oriental and Western elements. The staff of command conveyed his high rank in a way more easily comprehensible to the Western observer who was unable to fully understand the previously unseen, unfamiliar Other, perhaps only known through literary tales. It was a figurative compromise, depicting an alleged and imaginary reality. Addressed to the European observer alone, it followed the typical manner of representation of the Other in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. This kind of image also gives a good representation of the bloody and violent Tafiletta described by the English ambassador Lord Henry Howard, Earl of Arundel, in his letters to King Charles II. Howard, as recently argued by Matteo Barbano, had never actually met the sultan during his unsuccessful embassy to Morocco and his account may have resulted from reading an anonymous pamphlet published in London by the printer Samuel Speed in 1664. Entitled A Description of Tangier, The Country and People Adjoyning, with An Account of the Person and Government of Gayland, the Present Usurper of the Kingdome of Fez, it narrated the exploits of Abdallah al-Ghailan, an Arabian leader of Morocco.

The image of Ginnaeghel/Tafiletta was very popular and changed over time, taking on more and more European traits, especially in the depiction of his face, while he retained his exotic dress and the pose of an Oriental ruler (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Nicolas de Larmessin I, Portrait of Sultan Al-Rashid of Morocco “Cherif Muley-Arxid”, A Paris Chez P Bertrand Rue St. Jacques, à la Pomme d’Or, pres St. Severin, Avec Privil, du Roy’, ca. late seventeenth century, London, Victoria and Albert Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

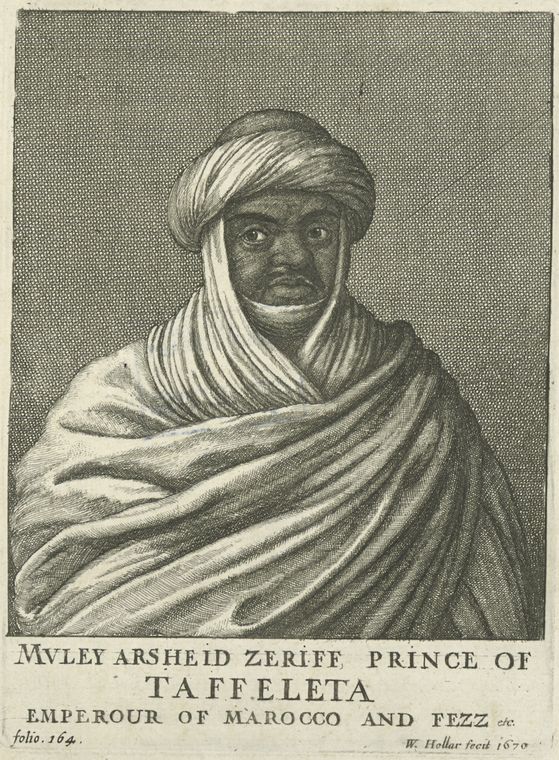

Tafiletta’s real face was drawn and engraved by one of the most prolific Baroque engravers, the Bohemian Wenceslaus Hollar, who was probably the only European artist who had the opportunity to meet him in Morocco (he had met him in 1670 when he participated in Lord Henry Howard’s diplomatic mission). In this engraving, inserted in John Ogilby’s Africa (1670) (Fig. 3), Tafiletta wears a long white tunic, wrapped around him from head to toe and suitable for the changing climate of the desert. It was a dress that struck the imagination of politician and writer Samuel Pepys, who in his Diary (1660–1670) wrote that the local people of Morocco looked like ghosts in their exotic white garments.

Figure 3: Wenceslaus Hollar, Portrait of Tafiletta, 1670, in J. Ogilby, Africa (London, 1670)

Interestingly, the standardized iconography of Tafiletta is also used to depict his brother Moulay Ismael, who succeeded him to the throne. In the text of Germain Mouette (1652–1691), a Frenchman who set sail to reach the Americas but was instead captured by pirates in 1670 and enslaved in Morocco for 11 years, we find an engraving in which he is portrayed with Oriental clothes and an idealized face with the European traits that characterized the image of Moulay Al-Rashid ibn Sharif. In the volume, entitled Histoire des Conquètes de Mouley-Archy connu sous le nom de Roy de Tafilet, et de Mouley Ismaël ou Semein, son frère et son successeur à présent régnant, contenant une description de ces royaumes, des lois, des coutumes et des moeurs des habitants, avec une carte du pays (Paris, 1682), Mouette provides an accurate account of the political situation of the kingdom during the seventeenth century and the traditions of the Moroccans. The historians regard it as a reliable source, but the same cannot be said about the chosen image of Moulay Ismael which is the product of a stratification that has its origins in the European Renaissance, like the drawing and engraving by Albrecht Dürer representing an Enthroned Monarch in “Oriental” Attire (New York, The Metropolitan Museum; Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum). It was one of Europe’s earliest attempts to portray a Muslim ruler, but it was more than simply a vague and ill-informed evocation of the customs of the East.

To represent the Other, a process of identification had to be put into motion, according to a principle that only legitimized an image based on elements deriving from the observer’s cultural sphere. An example of this communicative strategy is also found in the descriptions of the inhabitants of the New World written by Cristoforo Colombo and other travellers as they dealt with a reality they had never experienced before.

The European perspective often imposed itself on the representation of Otherness. To understand this process, we can also try to highlight how different representations building the Other’s identity converged and diverged, especially in the communicative process of engraved images. In my opinion, these images had a decisive impact on the structures and dynamics of building the Other’s identity and image within European culture.

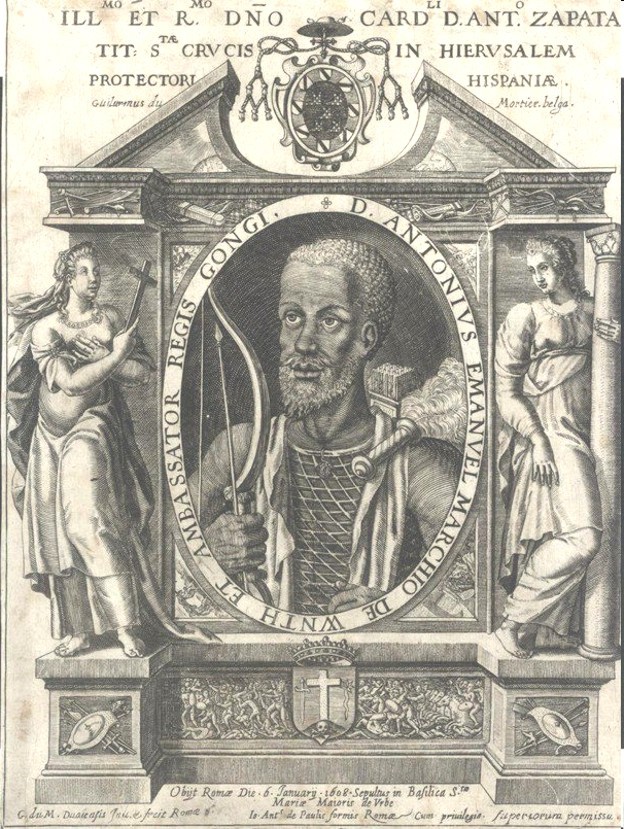

The abovementioned case of Ne Vunda is highly representative: in the engraving attributed to Raffaello Schiaminossi and published by Giovanni Antonio de Paoli in 1608 (Fig. 4), the unlucky Congolese ambassador, who died in Rome, is portrayed in European clothes.

Figure 4: Raffaello Schiaminossi, Portrait of Antonio Manuel Ne Vunda, 1608, London, The British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum

His bust is set in an oval above a skull, surrounded by an architectural frame with two allegorical figures on either side, and six biographical scenes, two of which dedicated to his perilous journey across land and sea, and four to his embassy in Rome. The last ones have their own captions, with the description of Ne Vunda’s arrival, his presentation to Pope Paul V, his deathbed anointing by the pope and his official funeral in the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. Executed immediately after Ne Vunda’s death, the engraving had three specific functions: to celebrate a unique event, namely the first Congolese ambassadorship to the Holy See; to commemorate the effigy of the noble ambassador through a portrait; and to spread news about the distant country from which he came. These functions are made explicit by the text inserted below the image, which notes that “Congo is a kingdom in the last parts of Africa, very rich in ivory but very poor in metals, so that snail shells are spent instead of money. Being in Ethiopia, this Kingdom produces black people like this Ambassador [who] used to go about there naked with a simple covering of woven palm fronds while in Rome he came in the dress that you see here”. A comparison with the Avvisi di Roma makes it clear that the text of the engraving reports what the chroniclers wrote, including the reference to the unusual use of Cypraea moneta, that is, shells as cash instead of metal coins.

The traditional garb worn by the ambassador matches the clothing represented in the sculptural portrait by Francesco Caporale and commissioned by Pope Paul V: in the depiction of the ambassador, it was decided to avoid European clothes, and to reproduce Congolese apparel, as had already been done in Ne Vunda’s portrait on the commemorative medal commissioned by the pope. As Kate Lowe explains, he wears a tunic of openwork raffia known as a kinzembe or zamba kya mfumu, that is, clothes reserved for persons of elevated standing, often combined with a cloak and a so-called “power bag” (nkutu a nyondo), always worn over the left shoulder. Indeed, the carved quiver seems to represent a nkutu that originally contained arrows.

The engraving and the sculpture show the two faces of Otherness. On paper, the format which obviously had a greater circulation, a Europeanized version was chosen to represent Ne Vunda, making him more similar to the observers. Holding the engraving in their hands, they could equate the ambassador’s figure with that of a Western noble man. Instead, the sculpted image, only visible at first in the Pauline Chapel, a place with restricted access to the public, the dignitary is represented in traditional clothes, to emphasize his peculiarity. Moreover, in line with the date of his death – 6 January, the day of the Epiphany – this representation symbolically endeavoured to compare him to Balthasar, one of the Magi.

The specific clothes allow us to correct the identification of Ne Vunda in the frescoes of the Sala Regia in the Quirinale Palace. Scholars generally identify him as the man in the second loggia on the north wall: the African native who appears between two guards wearing red-feathered hats in the Caravaggesque manner. However, the effigy that fits Ne Vunda’s royal status much better is the protagonist in the third loggia on the south wall. Generally identified as an Ethiopian man, a closer inspection reveals that he is wearing a Congolese woven raffia tunic and a yellow cloak.

This representation nevertheless differs from the mentioned images, namely the bust by Caporale, the engraving by Raffaello Schiaminossi and the fresco by Giovanni Battista Ricci depicting the encounter between the pontiff and Ne Vunda on his deathbed in the Sala Paolina in the Vatican Library. While Ne Vunda’s likeness in the Quirinale appears to be a freer interpretation of the unfortunate ambassador, it restores his political importance for the Borghese pontificate in the overall context of the pictorial cycle. The engraving with Nu Vunda in traditional dress made by Guillermus du Mortier, born in Douai, and printed by Giovanni de Paoli in 1608 (Fig. 5), must also be interpreted according to its political significance.

Figure 5: Guillermus du Mortier, Portrait of Antonio Manuel Ne Vunda, 1608, in F. Pigafetta, Relazione del Reame di Congo e delle circonvicine contrade… (Rome, 1591), Rome, Biblioteca Angelica, F.ANT II.7 24

The illustration is dedicated to the Spanish cardinal Antonio Zapata, who was struggling to get a foothold in the papal curia at the time. Ne Vunda had been detained in Spain for a long time before arriving in Rome and, coming from the Spanish Netherlands, the Flanders-Wallonian engraver thus tried to make an ally of the new cardinal inquisitor by dedicating the print to him.

Hence, knowledge of the Other was expanded and fostered by the production of printed images, which helped create a system for recognizing the different-to-oneself. The circulation of drawn or engraved representations aroused wonder, curiosity and at the same time helped broaden the cognition of Other cultures.

Bibliography

A. Amendola, L’altro in prospettiva. Quando l’arte aiuta a conoscere il diverso (Pisa, 2021).

M. Barbano, Within the Straits: Tangeri, gli inglesi e il Mediterraneo occidentale nella seconda metà del XVII secolo (Palermo, 2019).

D. Bindman, H. L. Gates, general eds, The Image of the Black in Western Art, 3, 1. From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque (Cambridge, MA, 2010).

Black is Beautiful: Rubens to Dumas, exhib. cat. (De Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, 26 July–26 October 2008), ed. V. Boele, E. Kolfin, and E. Schreuder (Zwolle, 2008).

A. Charant, Histoire de Muley Arxid, Roy de Tafilete, Fez, Maroc & Tarudent (Paris, 1670).

G. F. Davico, Vera Istoria del principe Tafiletto gran vincitore, et imperatore di Barbaria… (Bologna, 1670).

C. Fromont, “Foreign Cloth, Local Habits: Clothing, Regalia, and the Art of Conversion in the Early Modern Kingdom of Kongo,” Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material 25, 2 (May–August 2017), https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02672017v25n02d01-2

R. Gray, “A Kongo Princess, the Kongo Ambassadors and the Papacy,” Journal of Religion in Africa 29, 2, Special Issue in Honour of the Editorship of Adrian Hastings 1985–1999 and of His Seventieth Birthday, 23 June 1999 (May 1999): 140–54.

L. Lorizzo, Diversità sotto torchio. Rappresentare e divulgare l’immagine dell’Altro tra Rinascimento e Barocco (Pisa, 2022).

L. Lorizzo, “L’enciclopedia del mondo. Paolo V Borghese alla prova della ‘globalizzazione’ nella Sala Regia del Quirinale,” in Le arti e gli artisti nella rete della diplomazia pontificia, ed. M. Coppolaro, G. Murace, and G. Petrone (Rome, 2022), 171–78.

K. Lowe, “Visual Representations of an Elite: African Ambassadors and Rulers in Renaissance Europe,” in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, exhib. cat. (The Walters Art Museum, 14 October 2012–21 January 2013, The Princeton University Art Museum, 16 February–9 June 2013), ed. J. Spicer (Baltimore, 2012), 99–115.

H. Madar, “Dürer’s Depictions of the Ottoman Turks: A Case of Early Modern Orientalism?,” in The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye, 1450-1750. Visual Imagery before Orientalism, ed. J. G. Harper (Farnham, 2011), 155–83.

J. Ogilby, Africa, being an accurate description of the regions of Ægypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the land of Negroes, Guinee, Æthiopia, and the Abyssines, with all the adjacent islands … belonging thereunto … Collected and translated from the most authentick authors, and augmented with later observations; illustrated with notes, and adorn’d with peculiar maps and proper sculptures (London, 1670).

C. A. Rivington, “Early Printers to the Royal Society 1663-1708,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 39, 1 (September 1984): 1–27.

F. C. Springell, “Unpublished Drawings of Tangier by Wenceslaus Hollar,” The Burlington Magazine 106, 731 (February 1964): 68–74.

G. Tarantino, “Feeling White: Beneath and Beyond,” in Routledge History Handbook of Emotions Europe 1100–1700, ed. S. Broomhall and A. Lynch (New York, 2019), 302–19.

Biography

Loredana Lorizzo is Associate Professor of History of Modern Art at University of Salerno and teaches in the Department of Cultural Heritage. Her studies are focused on Italian, Flemish and Dutch art between XVI and XVII Century in Italy and Europe, with particular attention on Baroque painting and sculpture, the circulation of images and the history of 20th-century art criticism. She has been studying the mechanism of the modern art market and the role of merchants in Italy in the seventeenth century. Her most recent books are Per diletto e per profitto. I Rondinini le arti e l’Europa, Milano 2019 (with Cristiano Giometti) and Diversità sotto torchio. Rappresentare e divulgare l’immagine dell’Altro tra Rinascimento e Barocco, Pisa 2022.