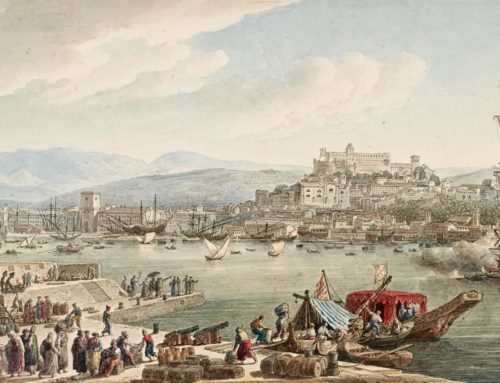

Eighteenth-century European views of the Ottomans reveal a complex set of politico-religious interests, as the Ottoman Empire declined militarily and gradually became less an object of fear. It was associated with certain clichéd images, in particular of despotism and fanaticism. Among these associations was the prevalence of the plague, which was endemic in many parts of the Ottoman empire, while after 1720 it no longer ravaged Europe. While this situation was often explained by the climate, many authors associated the prevalence of the plague with what they called Turkish “fatalism”, claiming that the Muslim belief in predestination prevented governments and individuals from taking any of the precautions against the disease used by Europeans. Thus the plague became part of the stock of anti-Turkish arguments, used in the justifications for political alignments in the Mediterranean. In the 1780s, an anti-Turkish author like the Frenchman Volney opposed those who supported the Ottomans as a bulwark against Russian expansionism, and argued for their expulsion from Europe and the Mediterranean; he went as far as identifying the Turks with the contagion, claiming that it was brought from Istanbul and had never been known in the Mediterranean before the arrival of the Turks.

Podcast 2: ‘The Turks and the Plague in the 18th Century,’ Prof Ann Thomson, A PIMo-CROMOHS Contagion Podcast

By Donal Hasset|2020-04-24T19:52:37+00:00April 24th, 2020|PIMo-CROMOHS 'Contagion' Video Podcast Series|