Newsletter December 2021

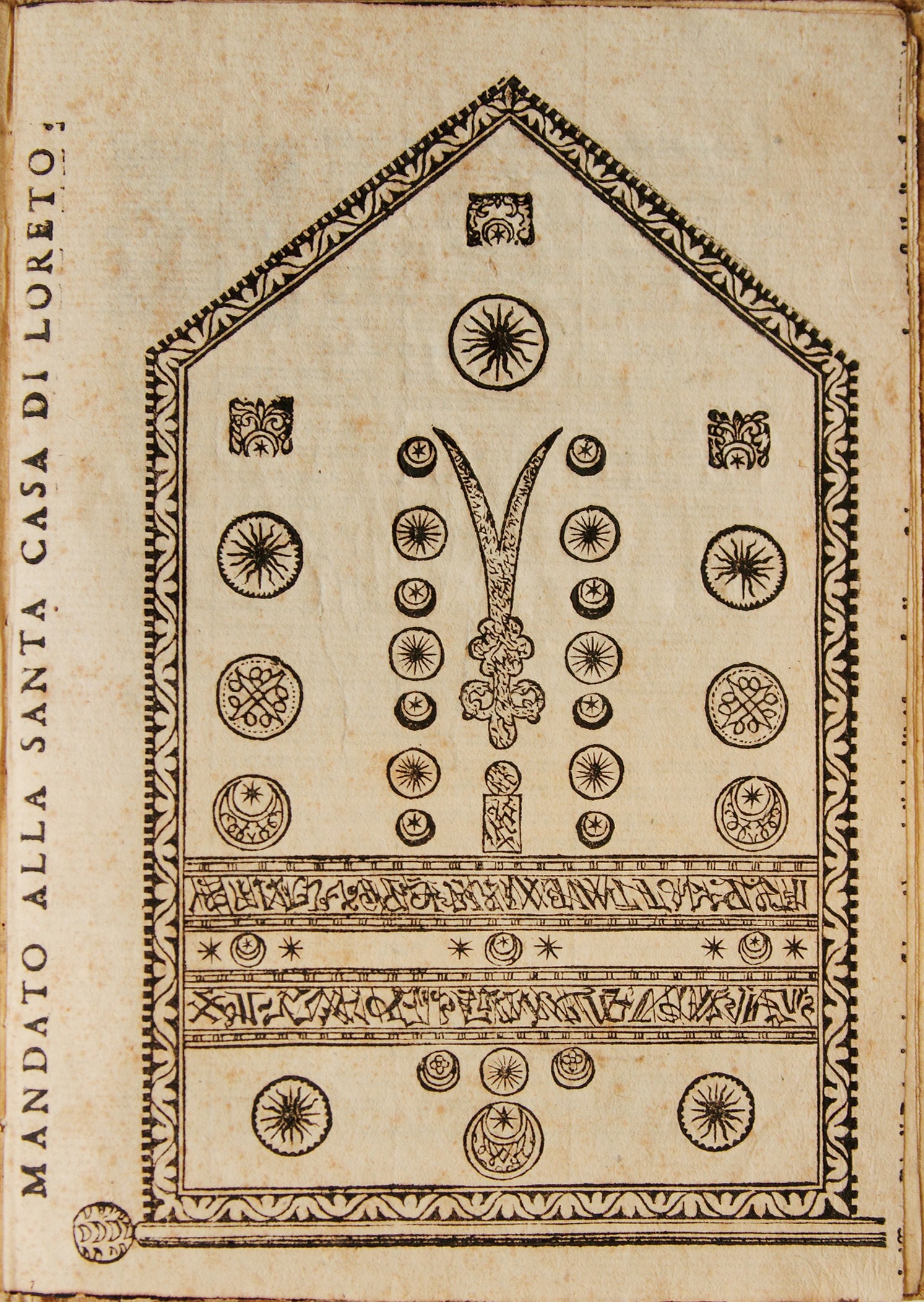

A Challenging but Productive Year Despite all the obstacles that 2020 has put in our way, our network has managed to adapt and continue to facilitate the production and exchange of top-class research on mobility in the Mediterranean. We successfully moved our major events online and developed new innovative strategies to facilitate the sharing of knowledge with network members and beyond. We launched a new podcast series, Contagion, exploring the history of pandemics and public health in the Mediterranean space. The series, co-produced with the Cyber Review of Modern Historiography (Cromohs) and edited by network member Dr David Do Paço, is available to listen to here: https://oajournals.fupress.net/index.php/cromohs/contagion Our Visual Reflection series, edited by Dr Paola von Wyss-Giacosa, offered fascinating insights into the history of mobility in the Mediterranean space through the analysis of visual and material culture. You can catch up with the wide range of contributions to it here: https://www.peopleinmotion-costaction.org/news-views/. This year has also seen the publication of a number of books and journal articles connected to research conduct as part of the PIMo project. You can find full details here: https://www.peopleinmotion-costaction.org/publications/ If you would like to [...]