On 15 September 1684, blank cannon shots greeted the arrival of an Ottoman flag in Loreto (Ancona). The silk flag (now in the Museum of Cracow) measures 639x321cm and displays an embroidered decoration consisting of Quranic verses, stars, medallions and the so-called Dhu al-Fuqar, a double-bladed sword associated with the figure of ‘Ali (599–661), cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad (d. 632).

The banner was a donation sent by the Polish king, John III Sobieski (1629–96), to the Marian sanctuary of Loreto. Before arriving in Loreto, it passed through Rome so that Pope Innocent XI (1611–89), who had received another sumptuous flag the previous year, could admire it. The flag came from the Siege of Párkány (today Štúrovo), a battle that followed the liberation of Vienna in autumn 1683, in preparation for the conquest of Buda that occurred in 1686.

The gift of the banner to the Marian sanctuary was an ex-voto. Since the victory in Lepanto (1571), the Madonna of the Rosary had assumed the role of custodian of the Catholic lands against the growing Ottoman threat. At the same time, because the Sanctuary of Loreto was believed to host the House of the Virgin, miraculously transported from Nazareth and saved from the Islamic conquest of the Crusader possessions in the Holy Land, it emerged as a holy place in which they would pray for and then commemorate victories against the Turks. An anecdote about the liberation of Vienna mentions the discovery of a portrait of the Madonna of Loreto. The triumphs against the ‘Turks’ were, therefore, often devoted to her figure.

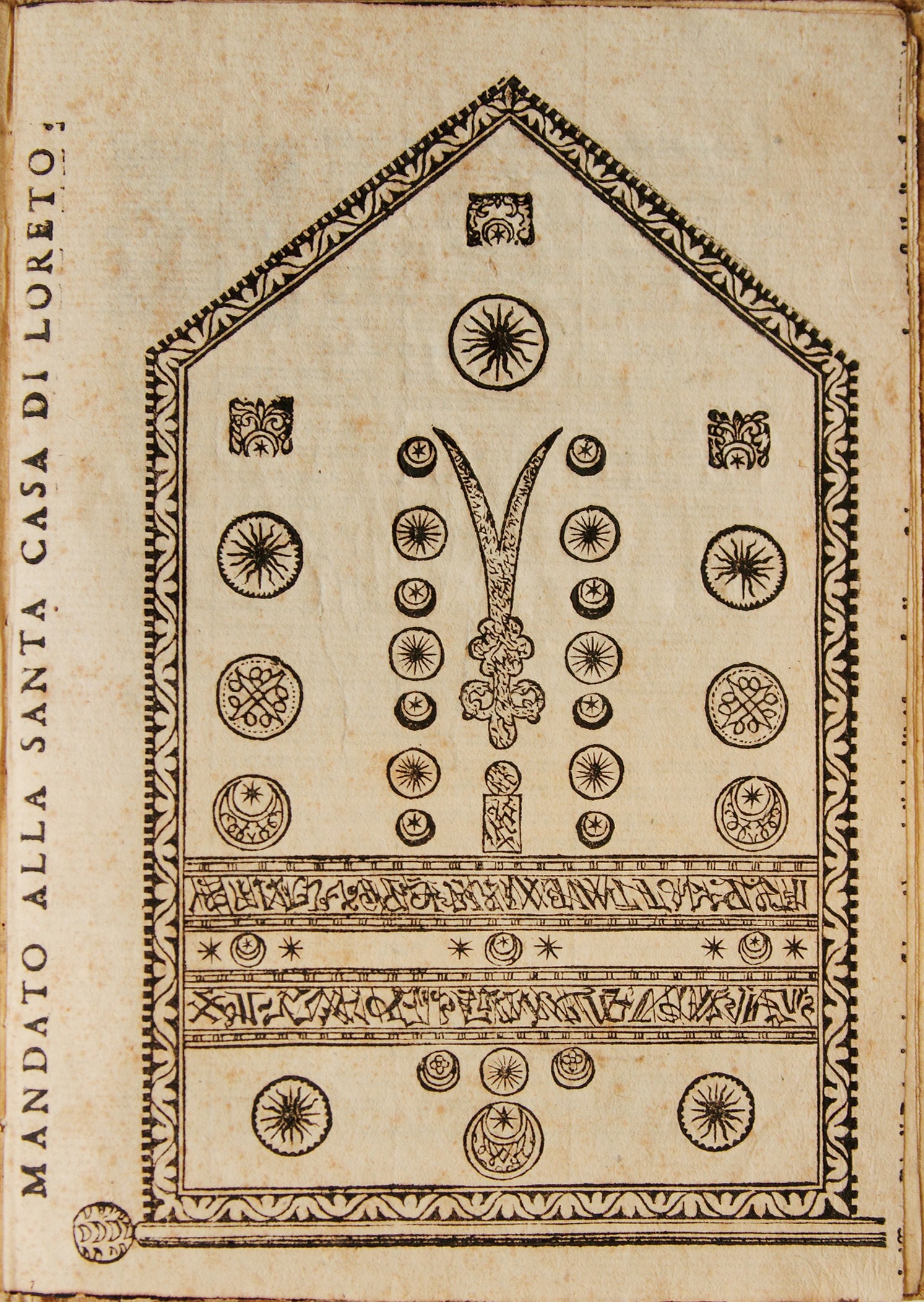

After the celebrations for its arrival in Loreto, the precious object was put on display in the church. More precisely, it stood on one of the pillars of the octagon that surrounded the marble ‘casing’ erected to protect the Holy House and the likeness of the Virgin Mary. Pope Innocent XI celebrated its conquest and donation by coining a commemorative medallion. Furthermore, following what had been done in Rome upon the flag’s arrival the year before, the local authorities promoted the publication of an opuscule to illustrate the conquered banner and explain its iconography.

Figure 1 Notification of the royal Turkish standard sent by the King of Poland to the Holy House of Loreto (Ancona 1684, p. 2) (Courtesy of the Archive of the Basilica of the Santa Casa, Loreto)

The opuscule on the Loreto banner follows the same compositional schema as the publication about the flag sent to Rome. The publication includes an engraving of the banner, a description of the ceremonies organised to celebrate the arrival of the Ottoman trophy and a translation of its Arabic inscriptions. At least three different publications are known: the six-page opuscule printed in Ancona, a single folio published in Foligno and an unidentified publication from Perugia.

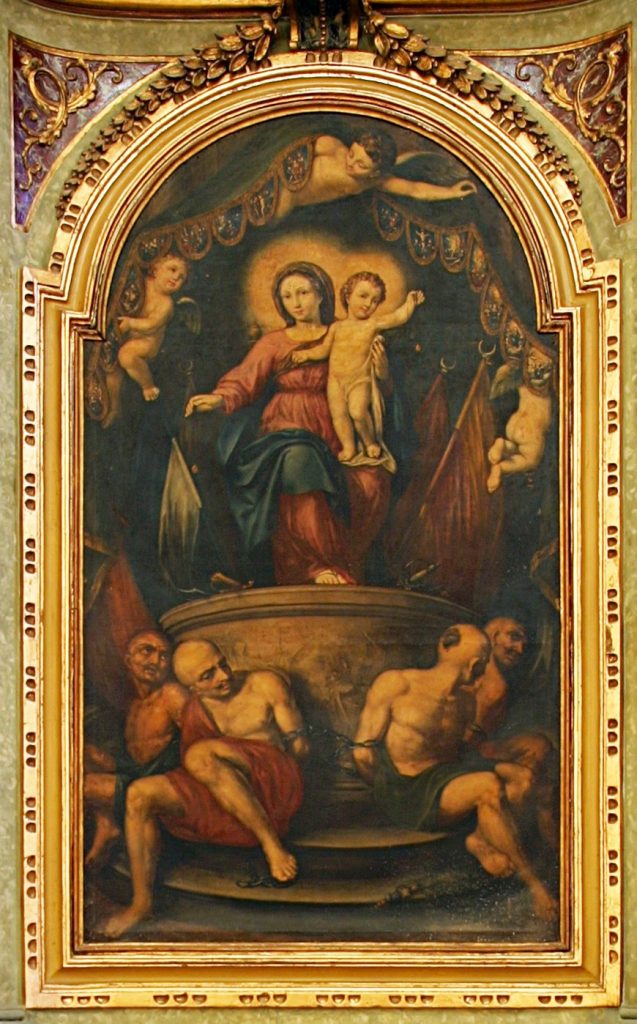

Following on from the example of Loreto, in the following 30 years, many churches and sanctuaries in the Marca Anconitana received Ottoman banners. Although the ceremonies were less sophisticated than in Loreto, all of the flags arrived as ex-votos donated by noblemen of cities such as Urbino, Fano and Osimo to thank the Madonna or a local saint for the protection granted during the battles along the Balkan frontier or on the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Seas. The role of the Virgin Mary – and more precisely of the Madonna of the Rosary – in protecting the believers from the Turkish threat is also portrayed in two paintings located in the Marche region. They display the Virgin Mary standing on a pedestal, with some Turkish prisoners and a group of Ottoman flags in the background, a direct reference to the spoils of war. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2 Madonna del Rosario, unknown author, Petriolo, Macerata, eighteenth century

In 1717, a procession brought two flags captured during a battle against the Ottomans and sent from Split, on the Dalmatian coast, to the Sanctuary of the Madonna della Rosa in Ostra (Ancona). The procession, which opened with a wooden statue of the Madonna of the Rosary flanked by the two flags, gave rise to the compositional schema of the paintings with the Madonna, the prisoners and the flags.

The figures of the Turkish prisoners tied to the pedestal were part of a common theme in early eighteenth-century Catholic Europe. Bare-chested and enchained, the men display the stereotypical features attributed to the Turks, with moustaches and shaven heads with a single clump of hair on the back. Very similar figures appear on the ceilings of Baroque palaces (especially in central Europe), but also in statuary groups, such as those in Livorno and Marino Laziale. Tiziano’s Philip II Offering the Infante Fernando to Victory (1573–75) was the point of departure for the iconography of the ‘Turkish prisoner’ as part of the spoils of war (including flags) offered to the emperor or holy figures.

Besides stereotypically depicting the Turks, the figures of the prisoners with the twisted chest and fastened hands were a reminder of the real prisoners enslaved during land and sea battles against the Ottomans. In the early modern Adriatic Sea, the term ‘Turk’ was used to mean a vast array of figures, which ranged from the soldiers of the Ottoman army to the corsairs who, backed by the Ottomans, looted the Italian coastline and threatened the fishermen operating in the open sea.

Where there were Ottoman-backed corsairs there were also those backed by the Church and Venetian army. The same was also true for the prisoners. Numerous Christian prisoners, kidnapped on the coasts or during inland incursions by Ottoman-backed corsairs, were exploited as rowers on the galleys or as an economic resource through the negotiation of ransoms. With the help of some confraternities, the families of those kidnapped collected money and rescued their loved ones from captivity. Their return was accompanied by the donation of ex-votos: a group of former slaves freed at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, for instance, donated their shackles and chains to the Sanctuary of Loreto. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3 Ex-voto showing a woman asking for the intercession of the Virgin Mary from the prow of a galley governed by a Turk, Sanctuary of Santa Maria del Monte, Cesena, beginning of the eighteenth century.

Ex-votos could remind of a miraculous event that saved lives or interrupted a period of captivity. The flags sent to sanctuaries back home dedicated the military victory to the intercession of the Virgin Mary or local saints into whose protection the soldiers put themselves. Besides the flags, dozens of ex-votos remembered the assistance provided by the Virgin Mary to prevent capture by the Turks. They often depicted maritime scenes, in which the enemies’ boats can be recognised thanks to the sailors’ dress and the flags with a crescent.

Between ca. 1480 and 1830, the Adriatic coast of the State of the Church became a frontier with the Ottoman-Turkish world. Confrontations occurred on a diplomatic level and in fierce battles. The conflict had repercussions on the daily life of the coastal population. From the great Sanctuary of Loreto to small local sanctuaries, intercessory prayers and the evidence offered by the ex-votos displayed within the churches helped neutralise the threat.