Visitors to the Museo Correr in Venice expect venezianità – and are duly rewarded by the museum’s exhibits and style of presentation: dogal portraits, paintings of the lagoon city, the piazzetta, the Rialto bridge or the church of Santa Maria della Salute. The collection, originally assembled during the first third of the nineteenth century, has since perpetuated an image of Venice’s past as historical grandeur. The late romantic vision of John Ruskin’s “The Stones of Venice” (1851) provided its programmatic foundations; today’s mass tourism with between 20 and 30 million yearly visitors reflects it in the same way as the Venice Time Machine project: a factory of dreams!

Figure 1: Marco Polo, c. 1880, H118cm, W78cm, D55cm, Museo Correr, Venice, inv. Cl. XIX 0172.

©Musei Veneziani.

Since 1881, the collection also contains a wooden, almost life-size seated figure, which doesn’t quite fit this impression (Fig. 1). Its eyes and facial traits, the moustache, the long robe as well as its gesture and the posture of the right leg and foot appear as if they stem from a different (dream) world. The golden colour throughout is equally irritating, as it intentionally fails to distinguish between the figure’s skin and its splendid clothing.

Inquiring into the history of this object, the following explores aspects of Venetian history that lie outside the typical imaginations of Venice. The museum’s attempt to identify the figure as Marco Polo, and thus to incorporate it into the narrative of venezianità, fails to do justice to the object and its history. A creation of the late nineteenth century, the object not only alludes to the most famous Venetian of the Middle Ages, but reveals itself as a representation of the colonial ambitions of a new nation state, the Kingdom of Italy, formed in 1861.

I: Geography as an Imagined Space

Following meetings in Antwerp (1871) and Paris (1875), the International Geographical Congress of 1881 was held in Venice. Principal initiators were the Società geografica italiana, established in 1867, and its first president, Count Cristoforo Negri. In 1880, Italy had become the latest European power to enter the race for colonies, and geography was the scientific endeavour of the hour. It served rather blatantly as a methodical justification of colonial ambitions. Scientific research and imperialism thus coalesced through international cooperation and national rivalries alike.

The impressive number of 1200 academic participants underlined the importance of collegial exchange in the scientific appropriation of the globe, especially those parts of Asia, Africa, and Oceania that had hitherto been less well known in Europe. The national significance of the conference was further reflected in its socio-political and cultural framings. Its official opening was attended by King Umberto I, his wife Margareth of Genua, and a great number of social and political luminaries, in whose honour banquets and soirées were held. All this was topped by an Esposizione geografica in the Napoleonic Wing of the Procuratie buildings on Piazza San Marco, which today houses the Museo Correr. Conference and exhibition, according to the contemporary observer Attilio Brunialti, “were meant to reflect the economic potential of a people, while highlighting what a people can do and is bound to do”.

The imperialist impetus was obvious. Not limited to the mere desire for territorial expansion, it also included a repertoire of attitudes towards the outside world, which were nourished by militarism, patriotism, feelings of racial superiority, and the belief in the national contribution towards human civilization. In light of Italy’s colonial juniority vis-à-vis Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, Spain or Portugal, the splendour of Italian culture came to be emphasised first and foremost.

It was amidst these circumstances that the seated figure made its way into the Museo Correr. A copy of a statue from the Buddhist Hualin temple in the southern-Chinese town of Guangzhou, it was created on behalf of Venice’s mayor – who bore the illustrious name of Dante di Serego Alighieri – and brought to Venice on the occasion of the Esposizione geografica. While the conference provided the scientific foundations for the discovery and imperialist appropriation of the world, the exhibition made a public display of Italy as a colonial power.

II. From Venetian Merchant to European Discoverer

The meaning of the statue does not derive from Marco Polo’s historicity as such, but from the European reception of his famous travelogue in the nineteenth century and various attempts to claim him as a national figure. The Milione travelled with Columbus on the Santa Maria in 1492 and framed the whole era of European expansion as an authoritative text. Its status arose not so much from a coherent narrative or the accuracy of its contents as from the promising tale of Eastern riches. The text’s wide circulation in several languages and more than twenty printed editions in the sixteenth century alone elevated the merchant from Venice to a historic role model of the European discoverer during the first age of globalization.

Following the Milione’s loss of appeal in the seventeenth century, the Enlightenment re-discovered Marco Polo as a travel writer. Around 1750, comprehensive compilations of travel literature emerged in England, France, and Germany, which proved highly popular. The Milione had its fixed place among this literature. In 1792, the book accompanied the first British delegation to China, helping to better localise their own experiences. The Milione’s reception initially focused on its language, on the basis of which its national belonging was negotiated. Yet, although Marco Polo was naturally considered an Italian in the Lazari-Pasini edition of 1847, the French orientalist Guillaume Pauthier claimed him for La Grande Nation. In the preface of his 1865 edition, he wrote: “car si Marc Pol est Italien par son origine, il est Français par adoption” (“if Marco Polo is Italian by origin, he his French by adoption”).

In essence, Marco Polo only became a colonial figure through a change in perspective in the reading of his travelogue. It was no longer his language as a national marker, but his geographical and historical knowledge of the Mongol Empire – from the Hindu Kush to the Pacific Ocean – that made him valuable to European readers, states, and scientific establishments. New editions were expanded with insights from more recent expeditions, which were incorporated into the historic text. This is most clearly evident in the maps featured in contemporary reprints. Enhanced by nineteenth-century cartographic knowledge, they seemingly reconstructed Marco Polo’s route of travel; essentially, however, they were instruments for the spatial mapping and appropriation of the colonial target zones in Asia.

The greatest highlight of the scientific editions was the 1871 English publication by Henry Yule. Its subtitle freely reveals the connections made between history and the present, scientific research and imperialism, as it presents the text ”with extensive critical and explanatory notes, references, appendices and full indexes, […] in the light of recent discoveries”. These additions also reflected the origins and the biography of the editor. Stemming from a family of military officers, Yule joined the East India Company as an engineer in 1840 at the age of seventeen, in whose service he oversaw the development of various civil and military projects. At the same time, he repeatedly participated in military campaigns, in the wars against the Sikhs just like during the Sepoy Uprising of 1857. Following his retirement in 1862, he returned to Europe, residing in England… and in Italy, where he began his research on Marco Polo.

Yule’s persona paradigmatically captures the essence of the European reception of Marco Polo: research in the historical geography of the Milione, pursued by a representative of the East India Company, an institution that like no other represented the genesis and political significance of European colonialism during the Victorian era. Yule combined scientific and colonial perspectives with his personal experiences as a traveller in India. These experiences were reflected in the editor’s imitation of Marco Polo himself. “The book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian” was published as a third edition in 1901, complemented by “a supplement, containing additional notes and addenda, with a memoir of Henry Yule by his daughter Amy Frances Yule and a bibliography of his writings”.

With each new edition spurring the reception of the Milione, Marco Polo became more palatable as a supposed historical role model for the agendas of European colonial powers, and essentially a colonial figure avant la lettre. The transformation from medieval traveller to colonial figurehead was driven primarily by the interpretations of European academies, which in turn nourished their own colonial ambitions while becoming instrumentalised by European powers competing for colonial possessions. Count Cristoforo Negri, the founder of the Società geografica italiana, regretted in his review of Yule’s edition, despite all due recognition, that the most dignified memorial to “the Italian Marco Polo” had been created by an Englishman. His exact phrasing neatly exposes the colonialist perspective so intrinsic to contemporary scientific discourse: “Yule ha sotratto agli italiani il lavoro: egli tiene il campo conquistato, e lo manterrà” (“Yule took over the work of the Italians; yet they hold the conquered territory, and they will keep it”).

The European colonial powers made use of Marco Polo’s travelogue by interpreting it as narrative model and spatial framework that supposedly provided a historical legitimization for their ambitions. While the historical sciences used the “invention of tradition” to legitimise the nation state, geography put it in the service of territorial expansion; through the reception of Marco Polo’s Chinese travels, it was possible to combine these two aspects congenially.

III: Italy in China

In 1866, Italy first established formal relations with the Qing rulers of the Middle Kingdom. Ostensibly, this step was intended to protect Italian missionaries. Yet Italy’s latest diplomatic endeavour was more than just religious politics. Western nations systematically used attacks on Christian missionaries as pretexts to demand new concessions such as the removal of trade barriers. The long-term goal of these policies, however, was to secure actual colonial possessions in China.

From a colonialist perspective, Guangzhou was the predestined location for this purpose. Situated in the province of Guangdong on the Pearl River Delta, the city traditionally represented – alongside Hongkong and Macau – the gateway to China in the South China Sea, and had for long been the centre of Chinese foreign trade. It fell to British colonial politics to first take note of this significance. In the Treaty of Nanking (1842), the first of the infamous “Unequal Treaties”, Britain cemented her control of Chinese ports from Guangzhou to Shanghai and thus achieved almost all her aims set forth at the beginning of the First Opium War.

It is an almost forgotten episode that Italy too controlled a colony in the area of Tianjin, 120 kilometres south-east of Bejing, more than 2,000 kilometres away from Guangzhou: 114 acres in size, a Little Italy in the north of China. The toponomy of this Italian district imagined Italy as a major European colonial power, an impero. The royal couple was represented by the Corso Vittorio Emanuele and the Piazza Regina Elena, the kingdom’s territorial claims in the northeast of Italy were upheld by Via Trento, Via Trieste, and Via Fiume, while Italian civilizational achievements were present with Via Dante, Via Matteo Ricci, and – last but not least – Via Marco Polo.

With its participation in the “Eight-Nation Alliance” against the Boxer Uprising (1900), Italy had positioned herself as a colonial power in China, and would stick to her fantasies of global power until 1947. In contrast to other colonial powers in Tianjin, Italy never succeeded in drawing any tangible benefits from the asymmetrical and far-ranging commercial freedoms stipulated in the Boxer Protocol. Neither did Rome’s political scene follow a corresponding strategy, nor did the Italian economy even meet the necessary requirements. Yet, Italy’s colonial presence in China mattered for reasons of internal politics. In the aftermath of the devastating defeat in the First Italo-Ethiopian War (1896), the colony in Tianjin helped recommit Italian public opinion to the politics of colonial expansion.

IV: In the Museum

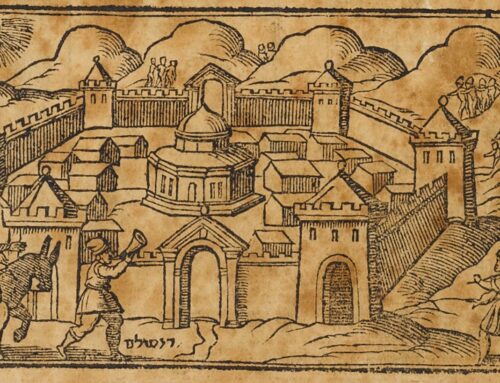

Against this backdrop, the seated figure of Marco Polo is of interest from a dual perspective of global and colonial history. In the Buddhist Hualin temple of Guangzhou, the original represents one of 500 Arhats, venerated ancestors who have made headway on the path to salvation (Fig. 2). Here too, just like in the Museo Correr, the figure appears out of line. The unusual headgear and collar, both of which appear European, presumably lie at the root of its identification as Marco Polo. The original from the Pearl River Delta and its copy in the Venetian lagoon are both entangled objects, although with different histories.

Fig. 2 View of the interior of the Temple of Five Hundred Genii in Canton,

Fig. 2 View of the interior of the Temple of Five Hundred Genii in Canton,

Hotz album 27, No. 438 / 317 (Shelfmark: Or. 26.590). ©Leiden University Library

In the heart of Venice, the gilded wood figure appears as an exotic object that documents Venice’s relational history with China, harking back to the thirteenth century. On a closer look, however, it appears more like a simulacrum; not necessarily one of the merchant Marco Polo, whose only surviving image is the one created by history. Rather, it is a simulacrum of Italian colonialism in China, which, densified by practices and discourses, materialised Italy’s colonial ambitions. The fulfilment of Italy’s longing for colonial possessions in China in the end had little to do with Marco Polo or the gilded figure in Guangzhou. As a space for the projection of imaginaries, the Italian colony in China nevertheless remained connected to the Venetian merchant.

The source of the statue’s identification as Marco Polo, and thus the responsibility for this short-cut from the Venetian Middle Ages to the era of Italian colonialism, remains subject to speculation; however, it does not seem far-fetched to assume that the likes of Dante di Serego Alighieri and Cristoforo Negri were as active in the creation of myths as in the founding of museums and scientific societies. Thus, the seated figure of Marco Polo also sheds light on the history of the museum and its role in the course of modern imperialism. Although a mere copy of a Buddhist representation of ancestry, the added meaning overwrites the materiality of the figure, and its historical attribution undoubtedly stood in the service of a colonial agenda. The entirely decontextualised presentation in the Museo Correr extends this impression to the present day.

Yet, its effects in the globalised world of the twenty-first century, in which China has a visible presence in Venice and Marco Polo reigns as a global cultural icon, are certainly different from the imaginations of an impero d’Italia. The circumstances and their underlying semantics have drastically changed, as exemplified not least by a public square in the Italian district of Tianjin. Formerly dedicated to Queen Elena, it nowadays bears the name of Marco Polo (马可波罗广场); it is unlikely, though, that anyone would still see this as an expression of Italian colonial ambitions.

This article, translated by Julius Morche, was first published in German in: https://mhistories.hypotheses.org/1617

Bibliography

I viaggi di Marco Polo Veneziano, tradotto per la prima volta dall’originale francese di Rusticiano di Pisa da Vincenzo Lazari, a cura di Lodovico Pasini. Venice, 1847.

Le Livre de Marco Polo, edité Guillaume Pauthier. Paris, 1864

The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, concerning the kingdoms and marvels of the East, newly translated and edited, with notes, by Henri Yule. London, 1871.

Borsa, Giorgio. Italia e Cina nel secolo XIX. Milan, 1961.

Brunialti, Attilio. Le colonie degli italiani. Rome, 1897.

Brunialti, Attilio. Il Terzo Congresso Geografico Internazionale tenuto a Venezia dal 15 al 22 settembre 1881. In: Nuova Antologia, Serie Seconda, XXIX, fasc. 19 (1 October 1881), pp. 373-422.

Brunialti, Attilio. L’esposizione Geografica Internazionale tenuta a Venezia nel settembre 1881. In: Nuova Antologia, Serie Seconda, XXX, fasc. 121 (1 November 1881), pp. 82-128.

Larner, John. Marco Polo and the Discovery of the World. New Haven, 1999.

Jacoby, David. Marco Polo, His Close Relatives, and His Travel Account: Some New Insights. In: Mediterranean Historical Review 21, No. 2 (December 2006), pp. 193–218.

Rando, Daniela. Venezia Medievale nella Modernità. Storici e critici della cultura europea fra Otto e Novecento. Rome, 2014.

Ryan, James R. Picturing Empire: Photography and the visualization of the British Empire. Chicago, 1997.

Strangio, Donatella. Italy-China Trade Relations: A Historical Perspective. Cham, 2020.

Urosevic, Uros. Italian Liberal Imperialism in China: A Review of the State of the Field. In: History Compass 11, No. 12 (2013), pp. 1068–1075.

Picture Credits

Fig. 1 Marco Polo, c. 1880, H118cm, W78cm, D55cm, Museo Correr, Venice, inv. Cl. XIX 0172. ©Musei Veneziani

Fig. 2 View of the interior of the Temple of Five Hundred Genii in Canton, Hotz album 27, No. 438 / 317 (Shelfmark: Or. 26.590). ©Leiden University Library