Throughout the centuries the Galata district in Istanbul has been a unique crossroad of multicultural both tangible and intangible heritage. Unfortunately, during the past sixty/seventy years the district was and still is at a constant attack and at risk of disappearing due to its neglect and lack of enhancement especially within the growth of the 21st century Istanbul’s metropolis.

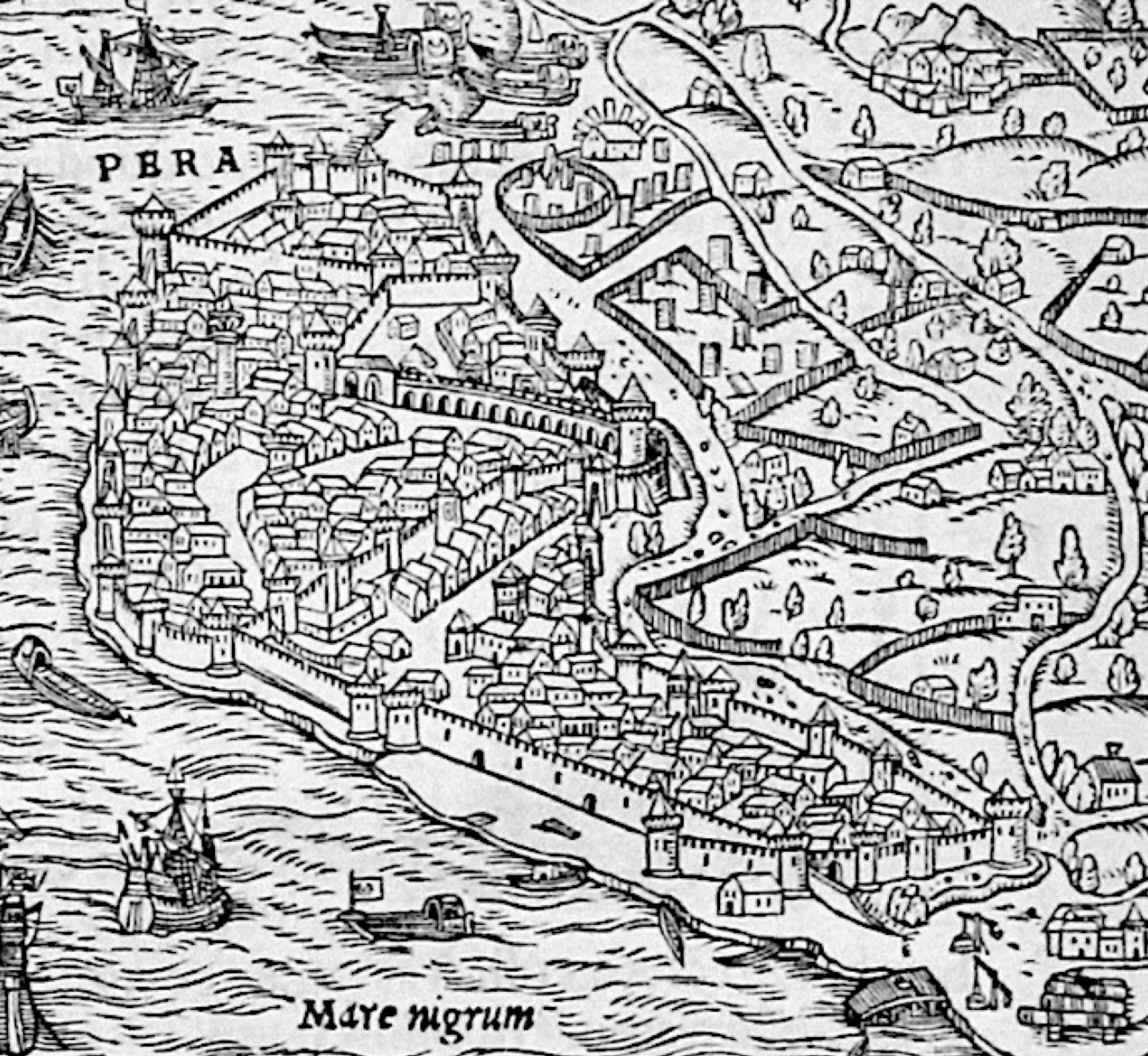

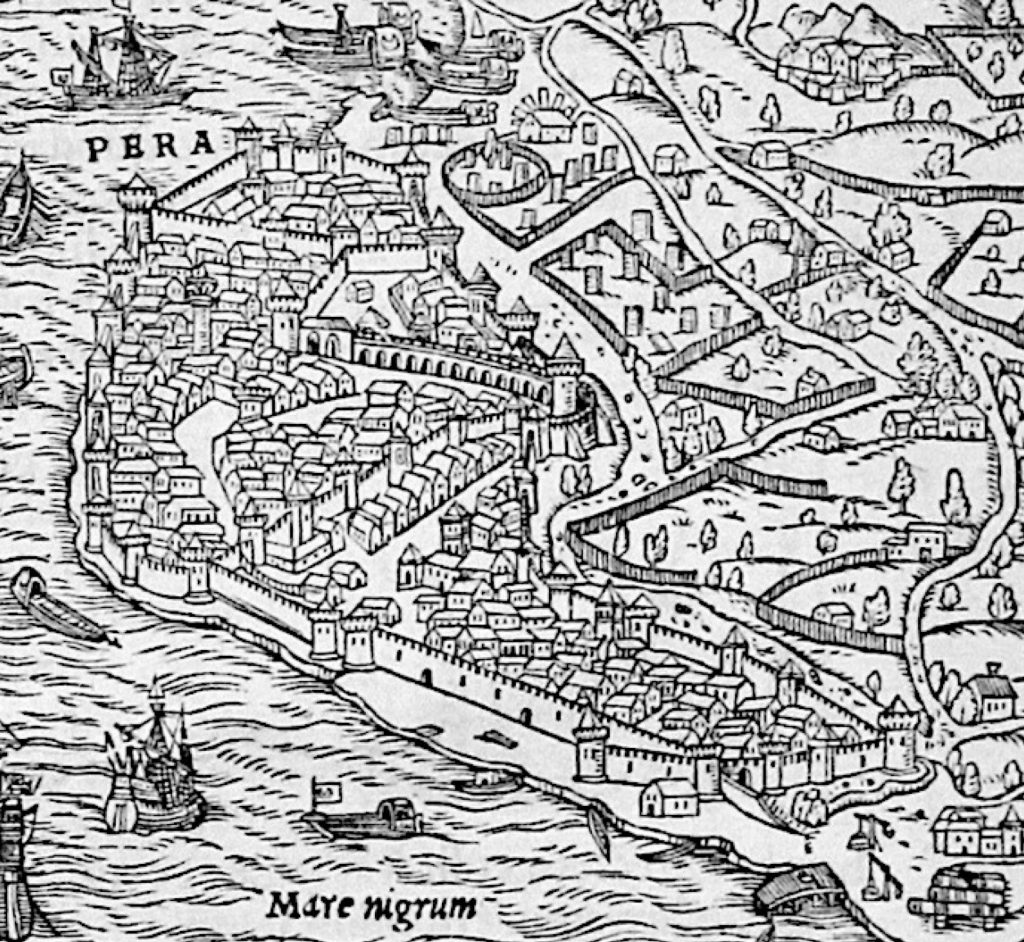

Since the ancient times Galata, which is today a neighborhood within the Beyoğlu Municipality, maintained a distinctive character in the city’s physiognomy, due to social and cultural contribution of its inhabitants and people who lived there, forming a unique urban environment throughout the centuries. During the Byzantine Empire, with the establishment of the Genoese colony, Galata district, or Pera as it was also known in ancient Greek and Roman time, grew as a more ‘Italian’ and Latin city inside the core of the oriental Orthodox world, building up a unique architectural environment within an urban texture adapted to the morphology and the orology of the territory, linked to the surrounding hills and to the sea, completely different and independent from the bigger center of Constantinople on the opposite site of the Golden Horn. This ‘foreign’ aspect of the colony was somehow implemented and preserved in the following centuries, when Galata started to be populated more and more by foreigners, the so called ‘Frenks’, who settled themselves in the area, bringing their own cultural aspects, customs, and traditions as well as religions. [Fig. 1]

Figure 1 The town of Pera from: Constantinopolitanae urbis effigies, in Sebastian Munster, Cosmographiae Universalis, Basel 1550. (Private Collection R.D.L).

After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, the town continued to maintain its cultural independence enriched by an even more colorful and fresh culture represented by the new Muslim Turk rules. The newcomers added new institutions and a new religion, and this foreign community was enriched by Jews and Arabs mostly coming from the Hispanic peninsula, as well as by the nomadic Turks who settled here. In the apogee of the Ottoman Empire Galata became a vital part in the commercial life of the city of Constantinople with its harbor and its natural predisposition for trade, defining a new ‘Levantine’ center in the Easter Mediterranean.

Due to the consolidation of the Empire and the ‘Ottomanization’ of the capital, these multiple cultural layers and peculiar characteristics were slowly englobed into a more severe system and the urban and architectural transformations of the following centuries carried the traces of the new rulers. Even under these conditions the town of Galata inside its enwalled structure was able to keep certain autonomy visible in the architectural contribution from the kaleidoscopic and melting pot community that coexisted and overlapped through the centuries.

In a very subtle and concrete way the historical periods from ancient Greek, passing through the Romans, the Byzantine, the Genoese and finally the Ottomans affected the urban fabric yet somehow never disturbed the preexisting heritage bequeathed by the different communities that were occupying the area. It is only in the last decades and mostly due to the modernization process that a disregard for and neglect of Galata’s centuries of multiculturalism emerged. The neglect of the contributions of the minorities, or “others” in the district is more evident in the present days rather than it was during its Ottoman past, at least up to the middle of the 19th century. In fact, in the previous historical periods urban modifications and adjustments were carried out in a more sensitive way without complete erasure of earlier layers other than some conversions or replacements, preserving the distinct character of the whole district.

Present-day Galata is largely the result of 19th and 20th century urban planning transformations and despite inevitable and rapid changes that occurred in the last 150 years in response to fires, earthquakes, and human interventions, a ‘genius loci’ is still present. The architectural cityscape of Galata, the various building typologies and styles are an unparalleled example of a multicultural and multi-ethnic milieu. Upheavals over the centuries transformed the appearance of the neighborhood, making it almost unrecognizable in today’s urban layout.

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the birth of the new Republic of Turkey, the Galata district slowly started losing its importance in the economy of the country. From a multicultural perspective, the population’s profile changed as well, and the cosmopolitan atmosphere that characterized Galata for almost seven centuries vanished, especially after the 1950s when inner immigration from Anatolia replaced the multi-cultural minorities who were slowly leaving the area. Today local inhabitants are almost exclusively Turkish and only few of the old local communities survive. In the last twenty years new foreigners started to revitalize Galata trying to bring new energy to the social redevelopment of the area but unfortunately, due to political and economic issues this trend slowly fades away.

Some of its architectural remains still preserve the multilayered character of the old Genoese town. Among the historical monuments that still exist in the district, the Galata Tower deserves special consideration as the only completely restored and renovated structure of the ancient system of the town walls. Instead, the other buildings or wall portions from the Genoese era that still exist in Galata are scattered throughout the district and in most of the cases neglected, hidden behind “modern era” buildings and deregulated urban developments, making of them just unimportant old, ruined elements in the environment. Strolling around the narrow streets and alleys of Galata not usually frequented by tourists, the compromised remains of the walls that once were part of the Genoese defensive system are in urgent need of effective interventions towards protection since many of the damages to these remaining parts of the walls are relatively recent [Fig. 2].

Figure 2 Remains of the Genoese walls nearby Azap Kapı, with the heavy infrastructural interventions for the new metro bridge. (Ivkovska, 2018)

Between the 1950s and the 1980s urban redevelopment intended to de-congest Galata by introducing new demolitions that resulted in an almost complete loss of the remains of the town walls. In 1958 an architectural masterpiece, the Raimondo D’Aronco’s Art Nouveau Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Paşa mosque built in 1903 in Karaköy square disappeared as a consequence of the enlargement of Galata’s main streets for vehicles. Most recently the remains of almost 200 meters of a Genoese wall have been damaged and compromised as heavy interventions in reinforced concrete and iron beams were introduced to support the entrance to a subway tunnel for the new metro line passing under the Galata hill.

Looking at the present-day conditions of the Galata’s architectural heritage, it seems that the local authorities don’t care about dilapidating this important trace of something considered to belong to the ‘Pre-Ottoman’ time or preserving in a proper manner the historic heritage of this multicultural “community”. Instead, searching for signs to confirm a strong national identity, administrators commonly overlook the past that has no direct connection to the Turkish or Ottoman heritage, even though throughout this process of urban development of Galata part of the Ottoman heritage was left out and suffered as well.

The multilayered architectural richness of Galata is not only limited to the Genoese heritage. The richness of the neighborhood consists of a conspicuous number of buildings dating from the Byzantine period, from the Latin domination. Many urban and architectural interventions dating from the Ottoman conquests until the beginning of the Republican era and beyond can be identified.

Figure 3 The Palazzo del Podestà in the present-day conditions. (Orlandi, 2019)

A variety of architectural structures are concentrated in the district, like the Palazzo del Podestà, a strong symbolic expression of the Genoese colony [Fig. 3], and the remains of the fortified walls; the mosques and converted buildings such as the San Domenico church converted into the Arab Mosque; the almost-disappeared building complex of the ‘Castello di Galata’ in Karaköy. Orthodox Rum and Armenian churches, as well as Jewish Ashkenazi and Sephardi synagogues spread around the small alleys of nearby Karaköy and in the surrounding of the Galata Tower. Public baths like the neglected one built by Sokollu Mehmet Pasha at Azapkapı; historical Ottoman residences and hans dating from the 18th and early 19th centuries with specific construction techniques in bricks and stones; an original 15th century bedesten built by Mehmet the Conqueror; hospitals like the Art Nouveau British masterpiece built just below the Galata Tower; convents as in the present-day French Saint Benoît School or the Austrian Skt. Georg School; the Ottoman Bank by the great Levantine architect Alexandre Vallaury, now partially transformed into Salt Galata cultural center; small fountains like the precious gem done by Raimondo D’Aronco, not far from the late 19th century Neo-gothic Italian synagogue; inns and corporate buildings, like the reconfigured Ceneviz Han or the St. Pierre Han; classical 16th century Ottoman masterpieces left by architect Sinan, such as the Rüstem Pasha Han [Fig. 4] and the Kılıç Ali Pasha and Sokollu Mehmet Pasha mosques in nearby Tophane and Azapkapı and many corporative and financial buildings along the Street of the Banks, like the Generali Han, the Minerva Han, the Sümer Bank, or the Karaköy Palas – nowadays are converted into luxury hotels for the benefit of the tourist sector – are important examples of the multilayered cultural richness of Galata and its nearest surrounding. The list of this historical heritage doesn’t end here. It includes many more buildings that help understand the kaleidoscopic amalgam of the urban environment of Galata.

Figure 4 The Rüstem Pasha urban inn, or caravanserai. (Ivkovska, 2017).

Environmental de-classification reduces the potential attractiveness of the district yet within such a composite context articulated by various stratifications, the neighborhood’s specific elements and landmarks may once more restore the area to life as an attractive and pulsing cultural center in Istanbul. In this place, as it was in the past, multiculturalism and diversity must be recognized as adding richness and as an intangible heritage that needs to be consciously protected and maintained for posterity. It seems important to define a precise asset about the Galata district in order to highlight and preserve the richness and multicultural origins of this important tangible heritage. We should indeed hope for a series of interventions aimed at ensuring a lasting and effective function for the entire area. Regardless of the architectural quality of the individual buildings, the historical and environmental heritage of the entire area must be reconsidered. This is imperative to avoid sporadic and isolated restoration interventions that in most cases are done for speculative purposes and not enough contextualized in a social frame.

Luca Orlandi is Assistant Professor at Özyeğin University, Turkey.

Velika Ivkovska is Assistant Professor at International Balkan University, Macedonia.